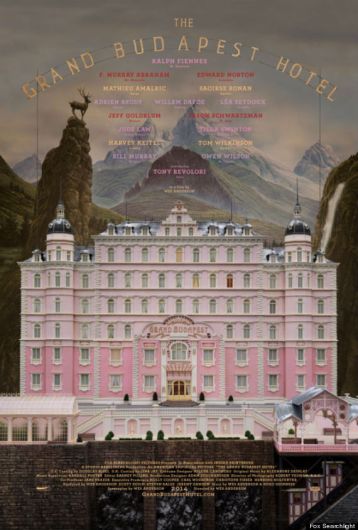

I’m currently reading a lot of Stefan Zweig in preparation for an upcoming Mookse and Gripes podcast — though, of course, also because I really enjoy Stefan Zweig’s work. It’s a thrill to see Zweig getting some more mainstream attention these days thanks to Wes Anderson’s latest film, The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), which, Anderson has stated, was inspired by the work and life of Zweig. Now, when I went to see the film I didn’t really know what to make of it when it was over (as is sometimes the case with a Wes Anderson movie), but in the following days and weeks, and especially thinking about it while reading Zweig, I’ve come to admire it a great deal (as is also often the case with Wes Anderson movies).

The Grand Budapest Hotel is a film about a non-existent past, the kind of past we are always wishing we could get back. In fact, the film has multiple layers of the past, each one degree further from reality.

When the film begins, it is the present day. A young girl takes a key and hangs it on a famous author’s statue. She sits to read his memoir. We take a step back to the 1980s, when that author (played here by Tom Wilkinson) is recording a kind of interview. Meanwhile his children pester him until he loses his cool. We step back again to 1968 when the author (now played by Jude Law) first visits the Grand Budapest Hotel, which, by this time, is in a state of disrepair. The lobby is rundown and nearly empty. The baths are murky and missing tile. Here he meets the mysterious owner of the hotel, a man named Zero Moustafa (F. Murray Abraham), who, the current lackluster concierge (Jason Schwartzman) says, comes to the hotel and stays in a tiny room that is smaller than the service elevator. What is going on here? Well, the elder Zero will tell us. And so we step back again, this time to settle in 1932.

There we find ourselves, four degrees removed from the present, each point of departure coming in the form of a story, with some tellers not even being present at the events being recounted. It fits perfectly, then, that 1932 is blatant artifice, something often charming in a Wes Anderson movie but here made thematically relevant. I’ll get more into that in a moment.

First, what is going on in 1932? The Grand Budapest Hotel is situated in the beautiful alps of the fictional Zubrowka. It’s in its glory years, just a year before Hitler comes to power — though, here, the threat of war and oppression is already real. Zero is a young lobby boy, working to perfect his trade under the tutelage of the great concierge, Gustave (played absolutely wonderfully by Ralph Fiennes).

Gustave himself longs for a past that, besides being past, is also probably nonexistent. He longs for it so much he attempts to characterize it, and even his favorite sexual delights are with the octogenarians. One of these octogenarians is the wealthy Madame Céline Villeneuve Desgoffe (or, Madame D., in one of Anderson’s nice calls to classic film, this to The Earings of Madame de . . ., directed by Max Ophuls, who also directed Letter from an Unknown Woman based on the wonderful story by Zweig (my thoughts here) (Madame D is played by Tilda Swinton)). Madame D seems to feel that something foul is coming, but Gustave ignores such developments. One day, Zero rushes to Gustave’s room to show him a newspaper reporting on WAR, but that’s also to be ignored. The salient bit of news is that Madame D is dead.

Off we go for an adventure that includes a heist, an alpine chase, a prison escape, a game of hide-and-seek in an empty museum (bringing to mind Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain), and a shoot out — each highly stylized. It’s well controlled, if a bit frenetic and intentionally jarring.

But the whole reason I am writing my thoughts on this film is to explore its relationship to Stefan Zweig. There’s more to the picture, of course, but let’s go this direction.

Zweig’s autobiography is entitled The World of Yesterday. He began writing it in 1934 which is also when he began his exile (covered wonderfully in George Prochnik’s recent Zweig biography, The Impossible Exile: Stefan Zweig at the End of the World). I’m simplifying here, but one thing Zweig cannot wrap his head around is how the past, in which he was a bon vivant could be so completely different from the present when everything was falling apart, irredeemably. Just a decade earlier he was passing his time in European literary high society, one of the most famous authors in the world, and now all that has fallen down around him. He and his wife leave everything behind, never to come back. His autobiography is an attempt to tell the story of that time in the irretrievable past.

The Grand Budapest Hotel is about the elusive, indefinable line between the irretrievable — indeed, never quite real — past and the brutal present. The past is presented with stylized allure, and we lull in nostalgia. Gustave ignores the doom surrounding him (something Zero, as a refugee from his own country’s war, does not do) to the point of being foolish (or suicidal). And yet, even in this fictitious world, brutality — physical brutality from the present state of affairs but psychological brutality that comes with disillusionment — break in. This film has several brief but shocking moments of violence that are quite uncharacteristic of Anderson’s former work. The violence has been criticized for bringing the viewer out of the film; I think that’s just the point, the film being the fictional past, the violence being the brutality breaking it down. The characters, who often say things like, “Oh, for heaven’s sake,” also drift into shocking vulgarity, which plays the same role as the violence: the pleasant façade slips. Many of the characters are just completely anachronistic. They don’t belong in this world at all. I’m thinking particularly of Harvey Keitel’s “let’s role” prison escape.

We rise from the past again at the end and are surprised by a few things:

First, we realize that each level was longing for some past that wasn’t quite what the character thought it was. Fiennes, we know, was living in the glory days before the war (but, also, perhaps back in the 1800s); Zero, as he slept in his old room he had as a low-level lobby boy, was longing for 1932 and the few years after (more on this in a moment); the old famous author, in the 1980s, was longing for the days in the 1960s when, young, he was out finding relics of the past in such places as the ruined Grand Budapest Hotel; and then in the present we have a young woman admiring that author, no doubt admiring the time in which he composed the memoir she’s reading.

Second, the story we’ve been told is not really the important one at all, at least, to Zero. The most meaningful moments of the past, to him, are on the fringe of this story, and really only get their start at its very end. We find ourselves another degree removed — one degree too far, as it turns out: that story is now lost since it’s not the one Zero recounted to the young author and is, therefore, not the one the author passed down in his memoir. It’s not the story the young girl is reading in 2014 as she visits the famous author’s statue, the famous author who, really, had nothing to do with 1932, either. Zero’s personal story of love and loss stays with him and is irretrievable.

It’s a strange film, one examining the issues that arise when one thinks on the past. In other words, it’s not as interested in examining the disconnect with the past as created by the passage of time as it is in examining the disconnect with the past that comes when we simply think of the past, replaying it in our head, and, to a lesser degree, what we do when we realize the time we want to live in is gone, if it ever was.

It’s not as good as sitting down and reading Stefan Zweig, but of course it’s not doing the same thing at all. It’s a few degrees removed from that.

I didn’t include this in the main post because it didn’t quite fit in with the rest of what I was going for, but listening to Michael Phillips of The Chicago Tribune talk about this film he brought up a line in Zweig’s Chess Story (which I reviewed here, back in the earliest days of this blog). It’s a nice description of Wes Anderson’s work in general:

If you haven’t read Chess Story, I recommend it.

Superb stuff, Trevor: haven’t seen this yet but this review makes it that bit more urgent: that shot of Fiennes is fantastic (and made me think of Terry Gilliam somehow’).

I think Anderson is an always intriguing director, a bit hit and miss these days, and I’m one of those predictable types who harks back to the glory days of Bottle Rocket and Rushmore (still his best films!). But this does look fascinating.

Looking back to the glory days, eh? Well, this is the movie for you, Lee!

Oh, and as for Fiennes: he’s tremendous here. I’m sure you liked him in In Brugges, and he shows again here just how adept he is at comedy. He’s perfectly cast and, well, perfect.

Great review. I hear it’s a good one and with some superb moments. I can’t wait to watch it myself.

Must check this film out! Also, wouldn’t it be interesting to have a post on writers famous everywhere except in US/UK? Zweig is considered a classic in China. Everyone’s read Letter from an Unknown Woman!

I really liked the film, and as a lapsed Anderson-phile, I was delighted to see him return to the form of Rushmore and Royal Tenenbaums. Fiennes is just great. You lost me a bit in your review at the end there…what do you think is the “important story” that doesn’t get passed on?

I have had World of Yesterday on the shelf for years…I must get to it.

I think the more important story, at least to Zero, is his relationship with Agatha. We are kind of led to believe that he bought the hotel and stayed in the quarters because of his loving relationship with Gustav, the story we hear, but really it’s because of the few happy years he spent with Agatha, after this story is over.

Does that make sense?

It does…I’d just disagree in that my feeling is that the film makes that pretty clear at the end…handled, admittedly, as a coda, but still one that resonates beyond the capers that have preceded it. It was quite shocking the way that was revealed, and it recast much of what had gone before.

I’m not sure what we disagree on, leroyhunter :-) . I know the film makes it clear, but my point is that that story is not shared. We see them meet, get out of a few scrapes, but we don’t see the few joyful years (or were they? perhaps that’s just nostalgia) they spend in the hotel after this story ends. I wrote:

That there’s a story there is mentioned, but the story is gone forever. Really, it was gone long before, lost in memory, but now even the memory is dead.

Watching this empasises how much Anderson loathes curves and kinks and loose threads and loves precision, meticulously mathematical, incorruptibly absurd symmetry. And it hits home just how much of a Chris Ware/Stanley Kubrick amalgam he is. Impeccably mounted in order to both preserve the unfolding events and safely box-in the lives, as though when the film ends all the characters lie snugly inside a plush velvet box like chess pieces, a shiny silver key ready to reopen them and reset them on their exact course. Anything troubling and time-honoured about them has been expunged; they’re not real and so can’t diminish. They’re emissaries of history and behaviour and nostalgic encapsulation, purposefully unreal, however recognisable. And no less charming for all that. Do you get that sense?

I agree and maybe disagree, Lee :-) . I think that Anderson is all of these things, but I do think he loves a degree of ambiguity and a sense of characters’ pasts and futures. For example, in Grand Budapest I think he’s always flirting with the line between precision and control (the things Gustave wants and values) and chaos (the war, the violence, the past, the uncertain future, the uncertainty, even, of the present), and that his style matches this to a degree.

I do agree they are “purposefully unreal,” at least as the story presents them. But again, whenever Fiennes swears or Abraham thinks about his short life with his wife, they seem real. The story we are watching is fake, but there’s a sense of depth and darkness that breaks down the stylistic barriers.

Does any of that make sense?