Blow-Up

d. Michelangelo Antonioni (1966)

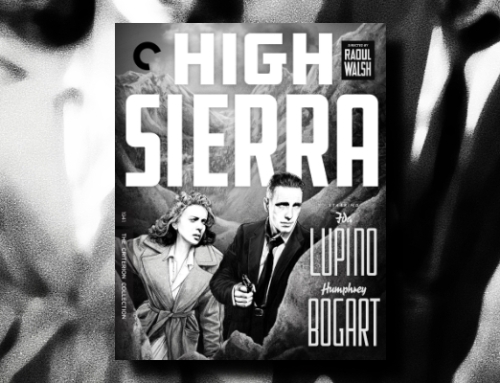

The Criterion Collection

There’s a story about the demise of the Motion Picture Production Code that goes something like this: In 1966, the embattled Code — moral guidelines governing what could and could not be included in a movie displayed for a public audience in the United States — was taking its final breath. Michelangelo Antonioni made a picture that didn’t pass the Code’s muster, didn’t even attempt to, but MGM, a large studio who had worked with the rules for decades, circumvented the Code and released the film regardless of the fact it did not have an approval certificate. It was the first time a large studio had done such a thing since the Code’s inception over thirty years before. The Code had been getting hit on all sides for years, but this film, for this story fittingly titled Blow-Up, incinerated it. The film won the 1967 Palme d’Or at Cannes, but that wasn’t a complete breakthrough. What was more surprising was that without the Code’s blessing the film went on to gross a lot of money in the United States, received Oscar nominations for screenplay and direction, and was picked as the best film of the year by the National Society of Film Critics. If a film could reach audience and get this acclaim without the Code, then what good was the Code? Rather than exist with no power, it ceased to exist soon after. This important land-mine in cinema history has just been released by The Criterion Collection in a lovely deluxe package.

There’s a story about the demise of the Motion Picture Production Code that goes something like this: In 1966, the embattled Code — moral guidelines governing what could and could not be included in a movie displayed for a public audience in the United States — was taking its final breath. Michelangelo Antonioni made a picture that didn’t pass the Code’s muster, didn’t even attempt to, but MGM, a large studio who had worked with the rules for decades, circumvented the Code and released the film regardless of the fact it did not have an approval certificate. It was the first time a large studio had done such a thing since the Code’s inception over thirty years before. The Code had been getting hit on all sides for years, but this film, for this story fittingly titled Blow-Up, incinerated it. The film won the 1967 Palme d’Or at Cannes, but that wasn’t a complete breakthrough. What was more surprising was that without the Code’s blessing the film went on to gross a lot of money in the United States, received Oscar nominations for screenplay and direction, and was picked as the best film of the year by the National Society of Film Critics. If a film could reach audience and get this acclaim without the Code, then what good was the Code? Rather than exist with no power, it ceased to exist soon after. This important land-mine in cinema history has just been released by The Criterion Collection in a lovely deluxe package.

For years I have known this basic story about Blow-Up (which is true but lacks a lot of fascinating detail and nuance about the demise of the Code), but I had never watched the film until this month when the new Criterion Collection Blu-ray showed up. Because I rarely heard about Blow-Up outside of its role in cinema history, I have always wondered if this film was great in and of itself. Is it a sacred cow that with the passing generations packs a softer punch fifty years after it helped usher in a new era of movie making, during which the very elements it thrust forward and that blasted the Code are now commonplace even in tame cinema? Or is it a true masterpiece that stands for the ages?

The basic setup is pretty straightforward. Thomas, a London-based fashion photographer (played by David Hemmings) does his job well but drives off for a momentary escape to Maryon Park. There he begins taking pictures of a couple. Lovers? Perhaps. And look at the nice retreat they’ve found in this peaceful park. When she sees Thomas with his camera, the woman (unnamed in the film but called Jane in Antonioni’s screenplay, played by Vanessa Redgrave) demands he give her the role of film. She even follows him to his studio, but he deliberately gives her the wrong role. He’s quite excited by the photographs, you see. They look like a peaceful way to end his photography book, which, he says to his editor, is otherwise quite violent. When he starts to develop the photographs, though, a story emerges in the details: Is that a man in the trees with a gun? Perhaps I prevented a murder. Wait, is that a dead body in the foliage? Perhaps I witnessed a murder.

With no clear answer, Thomas goes in “search of a mystery,” as novelist Italo Calvino said he should when Antonioni asked for some collaboration on the story. In other words, the mystery is whether there is any mystery at all.

David Hemmings as Thomas at Maryon Park

This setup has been used to great effect in subsequent films, particularly two I love that use sound recording instead of photography to set up a plot of paranoia: Francis Ford Coppola’s 1974 film The Conversation (which I reviewed here) and Brian De Palma’s 1981 film Blow Out. One major difference between Blow-Up and these two direct descendants is the ambiguity. The Conversation and Blow Out develop into exciting thrillers. Blow-Up ends with Michael witnessing, and eventually participating in, an invisible tennis match, a distinct lack of payoff we might be expecting in a thriller, but this is the very thing that, discarding all of the rest of what the film did in 1966, makes Blow-Up unique and surprising, profound in a different way than these other films.

Vanessa Redgrave as Jane, playing along to get the film

Blow-Up, for me, becomes a predecessor not only to the two great paranoia thrillers above but also to novelist Javier Marías’s great examinations of truth and lies and our ability to distinguish either in the part. If the photographs disappear, if there is no body, does our mind recognize that a crime was committed, or do we begin to doubt to the point we convince ourselves nothing happened, even if we witnessed it with our own eyes? How long can certainty exist when we are accosted by doubts and physical evidence is washed away?

After all, couldn’t the dead body have been an accident? Couldn’t the woman have wanted the role of film because it was evidence of her affair? And the gun was never that clear in the photographs to begin with. Take away the other photographs that combine to suggest a story, and there’s nothing there. It’s likely nothing happened.

And yet this potential nothing has the power to light up the otherwise coasting photographer.

So, yes, I am a believer in Blow-Up. It may be the Antonioni film I needed to approach his wavelength after failing to really appreciate his alienation trilogy of films: 1960’s L’Avventura, 1961’s La Notte, and 1962’s L’Eclisse, which also contain ambiguous mysteries and empty space. Indeed, I’m excited to revisit that trio of films with what feels like a personal breakthrough.

Beyond its role in movie history (which is fascinating and worthwhile in its own regard as well), beyond the portrait of mod culture mid-60s London (which is also wonderful to watch — Antonioni sets up the film by examining Thomas’s position in this exciting, constructed world of pleasure but little joy, and we get a disconcerting scene featuring The Yardbirds in their prime and before launching the careers of several of its members), Blow-Up is sophisticated, exciting, tense delight.

The long-desired Criterion Collection edition does not disappoint. It is a wonderful presentation of the film, which looks fantastic, along with lengthy, deep supplements. The disc includes two pieces on Antonioni’s artistic approach; an excerpt from the 2001 documentary Michelangelo Antonioni: The Eye That Changed Cinema; a 2016 documentary Blow Up of “Blow-Up”; old interviews with Antonioni, Hemmings (two of these, in fact), and Jane Birkin; and a new (lengthy!) conversation between photography curator Philippe Garner and Vanessa Redgrave. On the outside, it’s a nice looking deluxe package that includes a booklet with the original Julio Cortázar story; an in-depth essay, “In the Details,” by David Forgacs; a look at the films production by critic Stig Björkman; and a series of questions that Antonioni gave to painters and photographers to prepare for the film. This is an easy recommendation.

Great comments Trevor. As a child of the New Wave I vividly recall seeing “Blow-Up” on its theater release. I’m clearly biased but have to think the 60’s and 70’s may have been the most fertile, creative period in film history, pushing the envelope of narrative possibility, most prominently represented by France, Italy and Bergman in Sweden.

Seeing “Blow-Up” again not long ago on TCM for the first time in decades impossible to imagine any studio financing it today, unless to take a total flyer on someone of the presence that Antonioni had then. In fact the scene of successive blow-ups, mystery unfolding graphically in the images, is still seared in as a masterpiece of editing and tension line.

Thanks, Dennis. And, yes, that scene is tremendous. In fact, I wasn’t enjoying the film much at all, very much wondering if it was just a sacred cow, until that scene. Then, and with a rewatch, things fell together for me and I became a convert!

I think I felt as you did when I first saw “The Eclipse”. Sort of what’s the deal with Antonioni? Nothing happening in this movie. But seeing it again, also on TCM last winter, I was struck by how captivating it is. Something galvanizing in these characters that are so estranged from each other. Also, a particularly remarkable scene. In this instance the ending. Seven minutes or so of basically empty streets as I recall. You can’t take your eyes off it. It’s probably online.

Yes, that scene is one of the reasons I’ve always assumed my inability to meet Antonioni was me and not him. I love those seven minutes of absence. In fact, when saying above that I may have personally had a breakthrough, it’s because I finally feel I might be able to account for why those seven minutes are important to the film that comes before, and Blow-Up helped me make that connection.

Overall, I find this film (and Antonioni as a whole, particularly L’Avventura) a bit overrated. That said, it does pack some punch and has a number of vivid and memorable moments. The green-ness of the park and the way the viewer is invited to scan and search the image. The frolicking sex scene. The Yardbirds. I still think it reads a bit too much like postmodernism 101 (look, we’re voyeurs to a film about voyeurism!), and Antonioni’s best work by a good margin is in The Passenger (I’ve seen all the big ones except for Red Desert), but Blow-Up just has too much dead weight in the middle to hold up as a true classic. De Palma’s Blow Out is an improvement. The Conversation by Coppola is a descendant topically, but in terms of style and approach they’re quite different. Bergman famously said Antonioni was “suffocated by his own tediousness” and Truffaut said “Antonioni is the only important director I have nothing good to say about. He bores me; he’s so solemn and humorless.” I don’t know if I’m quite that disparaging or dismissive of him (again, largely because of The Passenger) but there’s a whiff of the honest truth coming from Francois and Ingmar. It will be interesting to see how Antonioni’s reputation ages in comparison to his peers.

Fun, kicking around these old films! I can sure see why Truffaut might have said Antonioni was solemn and humorless–he is! Quite unlike Truffaut. In fact, as I think of others of their generation they were all unlike each other. Personally, to compare Fellini and Godard and Resnais and Bresson and Bergman, to name a few is futile and kind of pointless, each voice was so distinctive. In the same way “Blow-Out, a very entertaining movie, comes as i recall out of quite different DNA than “Blow-Up”. DePalma was terrific but his narrative approach was dynamic, extroverted, a tension line directed toward a resolution. All it shares in my view is the deconstruction of a techno-product, in one instance sound recording in the other photography to answer a question, a question that is only suggested in “Blow-Up”. In other words as its been said, DePalma is a descendant of Hitchcock, Antonioni, maybe Camus and Beckett, an internal narrative toward an abstraction of aloness in the modern world. Heavy!

Good points, both of you. It should be noted, though, Sean, that Bergman disliked Antonioni’s work, except for Blow-Up, which he loved.

And, speaking of solemn and humorless. I don’t remember Bergman as the fount of knee-slapping hilarity either. In fact, just mention the name and my immediate image is heavy, lugubrious overcast, the sound of wind, Liv Ulman in close-up looking morbidly depressed, and a frigid-looking surf crashing rocks on a deserted shoreline. I wonder how any of these folks would make out in 2017 with CGI driven studio epics.

The best word for this movie is ‘overblown’. Sure, it’s great fun, with topless Vanessa Redgrave and the threesome romp, and it’s got some great camera-porn (the Nikon F1 and the ‘blad). But elsewise … a sophomoric ramble on the winding paths of ‘is it real, or is it only in my mind, and what’s the difference ?’ Plus there’s some predictable comment on well-minted snappers making £ out of grainy bw pics of the picturesque poor … but really, Thomas getting into his roller after a night in the Sally Army shelter ! … just a tad overdone.

It’s a fatuous, vacuuous, pretentious wankstain … in other words: A great Sixties Movie.

Congratulations TDMC!!

I think you may have just set a new standard for this blog with a self-indulgently written “overblown, fatuous and vacuous” comment. (I’m just guessing but I think you spelled “vacuous” with one “u” too many.) No easy accomplishment. Well done!

Now, if you’re still out there, care to inform us what a great “60’s movie” is? Are there any? And,of course why.you think so.

Counting on you!