Barry Lyndon

d. Stanley Kubrick (1975)

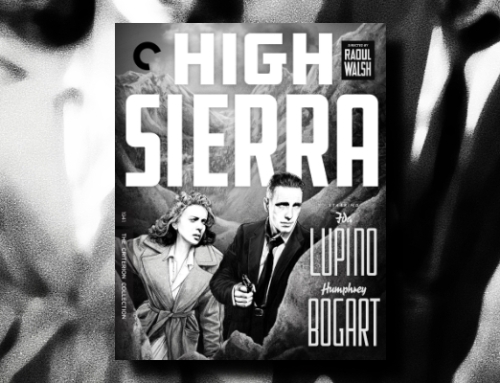

The Criterion Collection

After he finished 2001: A Space Odyssey, Stanley Kubrick set his sights back in time and began preparing to make a biographical film about Napoleon. He threw his heart and mind into this project, imbibing all of the research he could, determined to make it an opulent, realistic portrayal of one of histories most significant characters. However, the project was eventually scrapped for a variety of reasons, though principally because his financiers pulled the plug when Sergei Bondarchuk’s Waterloo did poorly, and Kubrick instead directed a visceral and controversial adaptation of Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange. The desire to realize his vision of Europe nearly two centuries in the past didn’t subside. With all of that research sitting around and playing through his mind, Kubrick finally found a new vehicle to bring that world to us; he would adapt William Makepeace Thackeray’s 1844 novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon. As much as I’d love to see Kubrick’s Napoleon film, I do not feel shortchanged. Barry Lyndon is a masterpiece and, for my eyes, one of the most beautiful and captivating and richly ambiguous films of all time. Today, the film is getting a deluxe home video release from The Criterion Collection.

After he finished 2001: A Space Odyssey, Stanley Kubrick set his sights back in time and began preparing to make a biographical film about Napoleon. He threw his heart and mind into this project, imbibing all of the research he could, determined to make it an opulent, realistic portrayal of one of histories most significant characters. However, the project was eventually scrapped for a variety of reasons, though principally because his financiers pulled the plug when Sergei Bondarchuk’s Waterloo did poorly, and Kubrick instead directed a visceral and controversial adaptation of Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange. The desire to realize his vision of Europe nearly two centuries in the past didn’t subside. With all of that research sitting around and playing through his mind, Kubrick finally found a new vehicle to bring that world to us; he would adapt William Makepeace Thackeray’s 1844 novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon. As much as I’d love to see Kubrick’s Napoleon film, I do not feel shortchanged. Barry Lyndon is a masterpiece and, for my eyes, one of the most beautiful and captivating and richly ambiguous films of all time. Today, the film is getting a deluxe home video release from The Criterion Collection.

The film feels like a luxuriously long novel. It begins with a title card reminiscent of eighteenth-century picaresques, saying: “By What Means Redmond Barry Acquired the Style and Title of Barry Lyndon.” There is an omniscient narrator, played by Michael Hordern, who often comes in to establish the scene or comment on the trouble that’s to come. Whether we fully trust the narrator, with his tone of condescension, is another question.

Of course, voice-over narration, particularly of the sort that may be said to explain what’s going on, does not work most of the time. Here, though, we get quickly experience the delights such a technique, done correctly and to add layers, can offer. The narrator sets the stage — and what a beautiful stage it is — by taking us to Ireland in the 1750s, at the moment Redmond Barry’s father is killed in a duel over some horses.

The narrator recounts this with understated humor at the ridiculousness of the situation, as tragic as it may be. At the same time as he notes this ridiculousness, the narrator lacks compassion. And, though Redmond Barry will do many things to deserve a lack of compassion, Kubrick nevertheless manages to present genuine loss. This sets up a competing tone for us in the audience: do we see Redmond Barry rise and fall through the eyes of the moralizing, ironic narrator? Or do we latch on to Redmond’s humanity and vulnerability, relating to his pain and even his failures, even as he works to repel us?

I happily accept such a host setting the stage and taking me through the film. This will not be, it turns out, a film that is concerned so much with surprising us with what happens in Redmond Barry’s lively, wandering life; it’s concerned with exploring the foibles, and consequent tragedy, these men can enact in this culture of the past that, nevertheless, feels as familiar as anything inherently human. This is a film that knows that, though we may not settle things with these honorable duels, that’s only because culture has shifted and not because humanity has changed.

Ryan O’Neal as the young Redmond Barry

When we first meet Redmond Barry — played with surprising perfection by Ryan O’Neal, who manages to be vulnerable and cold, nicely playing to the duel perspectives at work — he is playing cards with his older cousin, Nora Brady. To Redmond, Nora is the perfect object of his admiration. He wants to love her and be loved by her. For her part, Nora doesn’t mind the attention. However, whatever love she may or may not have for her naive, idealistic cousin, Nora is practical. She has no money. She’s becoming uncomfortably aged for a single woman. An English officer is interested. This is not the way life should go, thinks Redmond Barry.

A man’s life played out as a miniature upon the great beauty of this landscape

Refusing to accept the situation — and his cousin’s own explicit wishes — Redmond challenges the older officer to a duel. Some things in life are worth dying for. I’m just not entirely sure Redmond ever knows quite what those things are . . .

In a nice twist, the duel is a success for both parties. In the process, Redmond — played the fool, he learns later on — becomes a marked man and must flee. With more twists and turns of fate, he ends up fighting for both the English and the Prussian armies in the Seven Years’ War in Europe. The armies are so desperate for men, they don’t really care about their past. At first this gives him a place for belonging and allows him to keep up his fighting spirit.

But this is no life. Redmond Barry knows this, but those in power do not. To them, this is precisely the life Redmond Barry should have, and with gratitude. And so, we may sympathize with Redmond Barry. He’s young and stupid, and as clever as he is at getting out of scrapes, he’s never far from the next pitfall. What he really wants — what most of us want — is to rid himself of troubles, gain some power over his own life, and be free to pursue his own pleasure.

The film is famous for its innovative — and gorgeous — photography, especially for its techniques used to shoot in low, natural light

To pursue one’s own pleasure, though, requires one become a nobleman, even if seeking one’s own pleasure bears little relation to actual nobility. If we’ve empathized with Redmond till now, we are happy he may have finally found his luck, meeting, just as she’s becoming available, Lady Lyndon, played with a fragile hope that grows increasingly bitter by Marisa Berenson.

Marisa Berenson as Lady Lyndon, with Murray Melvin as Reverend Samuel Runt (if only another Warner Brothers film with Melvin as a churchman would come out on Criterion . . . )

But before long we see that Redmond, now officially Barry Lyndon, has little true nobility and love. He’s happy with a wife who, as the narrator says, serves as “the pleasant background of his existence.”

That phrase — “the pleasant background of his existence” — has always struck me, and not just because I question whether the narrator is simply skimming the surface, presenting the story we expect despite the moments where Kubrick and O’Neal offer a Barry Lyndon worthy of our sympathy if not our admiration. The film itself is gorgeous. A lot of Kubrick’s research for Napoleon involved tearing up art books, and the staging and colors and clothing he saw in those old paintings found their way into this film. Yet, for all of the beauty, Barry Lyndon’s life plays out in front of, and not as part of, the beautiful scenery. This is a nice contrast to a pair of films that inspired Kubrick’s technique (particularly in costume design, so much so that he hired the costume designer): Jan Troell’s The Emigrants and The New Land. In those two films, the characters are part of the landscape, often shot close up, toiling away. It’s ennobling. In Barry Lyndon, though, the landscape is — perhaps explicitly so, if we believe the narrator is also commenting on the filmmaking — just the pleasant background of Barry Lyndon’s existence. It’s beauty is not a part of him. He may take it for granted, focused instead on the duels and tricks that will get him one step further up society’s slippery ladder while those above drop things on him in disgust. And yet, that beauty exists apart from him and will continue to exist without him. I feel some sadness that Barry Lyndon barely seems to have his foot upon this beautiful world, so quickly does one thing lead to another as he fights to stay on the path he thinks is leading him to his prized destination.

Barry Lyndon is many things, but I do think Kubrick’s story is, at its heart, about a man who gambles with his life and fails . . . a man like many of us, victims of circumstance, filled with selfish deceit at our worst (and perhaps often). We can sit back and nod along with the narrator as he condemns the man who is so obviously reprehensible, comforting us while we admire the scenery and mock someone we think is below us. Or we can cry with a man who probably doesn’t deserve it. I’m not sure Kubrick is advocating some humane response; but I do think he is complicating the picture, giving it this depth, and poking his finger at any of us who simply take it all at face value. He’d probably poke his finger at someone saying there should be compassion, as well. What he probably wants, and this film works with those intentions, is to show us just how strangely complex — and despite that fairly unoriginal — we are. We come into this world, suffer and cause suffering, create opulence and fall into the mud, and we leave, while the pleasant background remains. How depressing. In the alternative, what a dramatic foreground — human, tragic, pathetic, admirable, heartbreaking, infuriating.

With all of this going on, and the beautiful canvas added in, the film is a treat and a treasure.

Indeed, The Criterion Collection edition is a treat and a treasure. The release contains two discs, one for the film (it’s over three hours long, so it needs some room) and one for the many, thorough supplements. It’s the first time the film has been given this kind of attention. While it has been out on Blu-ray before, it came with few supplements. And though that edition looked fine, it was released with the wrong aspect ratio, thus cropping off a bit of the top and bottom of every frame. That’s been fixed here, though it seems small, it does feel like a significant improvement.

This is definitely one of my favorite films of all-time, and this is the kind of release that does it justice and that continues to feed my admiration. I recommend without reservation.

Great review, Trevor, and choice of stills. Your favourite Kubrick?

Terrific review! I hadn’t seen the film since its theatrical release over 40 years ago when I caught it on TCM last winter sometime. Really is monumental, complex, visually rapturous (a pretentious word but I like it) totally captivating for all 180 minutes or however long it is. Drops us into a new world a few centuries past. Yup, Ryan O’Neal is perfect!

Thanks for writing about it!

Thanks for your thoughts, too, Dennis. Rapturous is apt!

Lee — oh, I have never tried to do this. Definitely have to put 2001 at the top. After that I think it’s Barry Lyndon, or whichever I’m thinking about at the time! No, I really do think my second favorite is Barry Lyndon because I’ve felt that for some time, even before this revisit, so it’s not just recency bias. After that, though, things get bit muddled with The Shining and Dr. Strangelove all clamoring for the third spot on my ranking (and recency bias might push them above Barry Lyndon on any given day I watch them).

Below that I still think they’re all masterful.

An impossible ask – sorry! I love Paths of Glory and that was my favourite for a good while, but Lyndon is a masterpiece…The Shining also…Strangelove…it has to be 2001. Why fight it?