It’s that time of year again! Best Translated Book Award time! Below is the 25-book strong longlist, just announced over at The Millions, which includes a few of my favorites (Compass, My Heart Hemmed In, and Radiant Terminus) as well as many I have not read yet.

It’s that time of year again! Best Translated Book Award time! Below is the 25-book strong longlist, just announced over at The Millions, which includes a few of my favorites (Compass, My Heart Hemmed In, and Radiant Terminus) as well as many I have not read yet.

There are some notable books that missed the cut: Domenico Starnone’s Ties, Mihail Sebastian’s For Two Thousand Years, and Patrick Modiano’s Sundays in August. At the same time, this is a varied list, with many newcomers.

As a reminder, books are eligible for this year’s prize only if they were published in English in the United States last year for the first time ever. So, no re-translations are eligible. All of us are just getting to know these, even if they were written decades ago and the authors have long since passed on (a handful of the authors below are dead). Go check them out!

The ten finalists will be announced on May 15. The winner will be announced on May 31.

Incest

Incest

by Christine Angot

translated from the French by Tess Lewis

(France, Archipelago)

Purchase from Amazon.

A daring novel that made Christine Angot one of the most controversial figures in contemporary France recounts the narrator’s incestuous relationship with her father. Tess Lewis’s forceful translation brings into English this audacious novel of taboo.

The narrator is falling out from a torrential relationship with another woman. Delirious with love and yearning, her thoughts grow increasingly cyclical and wild, until exposing the trauma lying behind her pain. With the intimacy offered by a confession, the narrator embarks on a psychoanalysis of herself, giving the reader entry into her tangled experiences with homosexuality, paranoia, and, at the core of it all, incest. In a masterful translation from the French by Tess Lewis, Christine Angot’s Incest audaciously confronts its readers with one of our greatest taboos.

Her books are an incantation, biblical in their onrush of verbs, nouns, names, and deliberate repetitions (yes, I, too, repeat myself) in the service of rhythm and camouflage, compelling you to read on, for sound, for cadence, for poetry. I’m a woman of no convictions, she says. I’m a woman of strong convictions, she also says. It’s as if she were saying: The two of us (you and I, reader) are in a maze of my creation; let’s see how you, we, fare. She puts everything on the line; she is not embarrassed. She tells us, “Incest is the book in which I present myself as a real shit, all writers should do it at least once.” She lays herself bare and invites us to take a bite. ~Tsipi Keller, Asymptote

Suzanne

Suzanne

by Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette

translated from the French by Rhonda Mullins

(Canada, Coach House)

Purchase from Amazon.

Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette never knew her mother’s mother. Curious to understand why her grandmother, Suzanne, a sometime painter and poet associated with Les Automatistes, a movement of dissident artists that included Paul-Émile Borduas, abandoned her husband and young family, Barbeau-Lavalette hired a private detective to piece together Suzanne’s life.

Suzanne, winner of the Prix des libraires du Québec and a bestseller in French, is a fictionalized account of Suzanne’s life over eighty-five years, from Montreal to New York to Brussels, from lover to lover, through an abortion, alcoholism, Buddhism, and an asylum. It takes readers through the Great Depression, Québec’s Quiet Revolution, women’s liberation, and the American civil rights movement, offering a portrait of a volatile, fascinating woman on the margins of history. And it’s a granddaughter’s search for a past for herself, for understanding and forgiveness.

We’ve become conditioned, in the books we read and the films we watch, to our heroines achieving some form of redemption, however problematic they might be and however spurious that redemption. But as you might have guessed, Suzanne isn’t that kind of novel, and that’s because Suzanne wasn’t that kind of person. ~Ian McGillis, The Montreal Gazette

Tómas Jónsson, Bestseller

Tómas Jónsson, Bestseller

by Guðbergur Bergsson

translated from the Icelandic by Lytton Smith

(Iceland, Open Letter Books)

Purchase from Amazon.

A retired, senile bank clerk confined to his basement apartment, Tómas Jónsson decides that, since memoirs are all the rage, he’s going to write his own—a sure bestseller—that will also right the wrongs of contemporary Icelandic society. Egoistic, cranky, and digressive, Tómas blasts away while relating pick-up techniques, meditations on chamber pot use, ways to assign monetary value to noise pollution, and much more. His rants parody and subvert the idea of the memoir—something that’s as relevant today in our memoir-obsessed society as it was when the novel was first published.

Considered by many to be the ‘Icelandic Ulysses‘ for its wordplay, neologisms, structural upheaval, and reinvention of what’s possible in Icelandic writing, Tómas Jónsson, Bestseller was a bestseller, heralding a new age of Icelandic literature.

It’s not the most appetizing of visions, but Bergsson’s shaggy (and, in a couple of instances, carefully shaven) dog stories have a certain weird charm, even as it develops that Jónsson has discovered one great raison d’être for writing a memoir: revenge. ~Kirkus

Compass

Compass

by Mathias Énard

translated from the French by Charlotte Mandell

(France, New Directions)

Purchase from Amazon.

As night falls over Vienna, Franz Ritter, an insomniac musicologist, takes to his sickbed with an unspecified illness and spends a restless night drifting between dreams and memories, revisiting the important chapters of his life: his ongoing fascination with the Middle East and his numerous travels to Istanbul, Aleppo, Damascus, and Tehran, as well as the various writers, artists, musicians, academics, orientalists, and explorers who populate this vast dreamscape. At the center of these memories is his elusive, unrequited love, Sarah, a fiercely intelligent French scholar caught in the intricate tension between Europe and the Middle East.

With exhilarating prose and sweeping erudition, Mathias Énard pulls astonishing elements from disparate sources — nineteenth-century composers and esoteric orientalists, Balzac and Agatha Christie — and binds them together in a most magical way.

So much now weighs on Franz — inescapably, all the history he’s accumulated, but personally, too, his own confrontation with mortality (and, before that, the promise of what should be, medically, an ugly decline) as well as the literally out of reach woman whom he can’t get out of his thoughts, a debate-partner (among much else) debating now at such a distant remove. Énard manages to make what is essentially this sleep-deprived protagonist’s monologue consistently entertaining — no wonder he can’t sleep, with all this bubbling in his mind — with enough of the human to the story to make even the more obscurely scholarly go down comfortably easily.

A fine piece of writing, and a very enjoyable work. ~M.A. Orthofer, The Complete Review

Bergeners

Bergeners

by Tomas Espedal

translated from the Norwegian by James Anderson

(Norway, Seagull Books)

Purchase from Amazon.

Bergeners is a love letter to a writer’s hometown. The book opens in New York City at the swanky Standard Hotel and closes in Berlin at Askanischer Hof, a hotel that has seen better days. But between these two global metropolises we find Bergen, Norway—its streets and buildings and the people who walk those streets and live in those buildings.

Using James Joyce’s Dubliners as a discrete guide, celebrated Norwegian writer Tomas Espedal wanders the streets of his hometown. On the journey, he takes notes, reflects, writes a diary, and draws portraits of the city and its inhabitants. Espedal writes tales and short stories, meets fellow writers, and listens to their anecdotes. In a way that anyone from a small town can relate to, he is drawn away from Bergen but at the same time he can’t seem to stay away. Espedal’s Bergeners is a book not just about Bergen, but about life—in a way no one else could have captured.

Bergeners is unusual (non)fiction, but often fascinating and certainly well-done; it’s also a very moving personal work, with the feel and appearance of still waters, running oh so deep. ~M.A. Orthofer, The Complete Review

The Invented Part

The Invented Part

by Rodrigo Fresán

translated from the Spanish by Will Vanderhyden

(Argentina, Open Letter Books)

Purchase from Amazon.

An aging writer, disillusioned with the state of literary culture, attempts to disappear in the most cosmically dramatic manner: traveling to the Hadron Collider, merging with the God particle, and transforming into an omnipresent deity — a meta-writer — capable of rewriting reality.

With biting humor and a propulsive, contagious style, amid the accelerated particles of his characteristic obsessions — the writing of F. Scott Fitzgerald, the music of Pink Floyd and The Kinks, 2001: A Space Odyssey, the links between great art and the lives of the artists who create it — Fresán takes us on a whirlwind tour of writers and muses, madness and genius, friendships, broken families, and alternate realities, exploring themes of childhood, loss, memory, aging, and death.

Drawing inspiration from the scope of modern classics and the structural pyrotechnics of the postmodern masters, the Argentine once referred to as “a pop Borges” delivers a powerful defense of great literature, a celebration of reading and writing, of the invented parts — the stories we tell ourselves to give shape to our world.

Admittedly, the question of whether The Invented Part is a novel was a rhetorical exercise meant to draw out certain aspects of this text. Of course, it is a novel. It is, however, something much more: a resounding refutation of the assertion that the novel is dead, and a statement of how omnivorous and adaptable the form is. ~George Henson, Quarterly Conversation

Return to the Dark Valley

Return to the Dark Valley

by Santiago Gamboa

translated from the Spanish by Howard Curtis

(Colombia, Europa Editions)

Purchase from Amazon.

Santiago Gamboa is one of Colombia’s most exciting young writers. In the manner of Roberto Bolaño, Gamboa infuses his kaleidoscopic, cosmopolitan stories with a dose of inky dark noir that makes his novels intensely readable, his characters unforgettable, and his style influential.

Manuela Beltrán, a woman haunted by a troubled childhood she tries to escape through books and poetry; Tertuliano, an Argentine preacher who claims to be the Pope’s son, ready to resort to extreme methods to create a harmonious society; Ferdinand Palacios, a Colombian priest with a dark paramilitary past now confronted with his guilt; Rimbaud, the precocious, brilliant poet whose life was incessant exploration; and, Juana and the consul, central characters in Gamboa’s Night Prayers, who are united in a relationship based equally on hurt and need. These characters animate Gamboa’s richly imagined portrait of a hostile, turbulent world where liberation is found in perpetual movement and determined exploration.

His novel follows five seemingly unrelated story lines: a brilliant but emotionally scarred female poet; a writer turned one-time diplomat (simply referred to as Consul); an Argentine neo-Nazi evangelist; a priest-turned-rebel; and the celebrated French poet, Arthur Rimbaud. The novel is divided into two parts and an accompanying epilogue over the course of which we become well acquainted with the journeys and miraculous crossing of paths of its protagonists. Gamboa seamlessly weaves together biography and fiction, at times even borrowing from his own, quite fascinating life. ~Amir Soleimanpour, Los Angeles Review of Books

Affections

Affections

by Rodrigo Hasbún

translated from the Spanish by Sophie Hughes

(Bolivia, Simon and Schuster)

Purchase from Amazon.

A haunting novel about an unusual family’s breakdown—set in South America during the time of Che Guevara and inspired by the life of Third Reich cinematographer Hans Ertl—from the literary star Jonathan Safran Foer calls, “a great writer.”

Inspired by real events, Affections is the story of the eccentric, fascinating Ertl clan, headed by the egocentric and extraordinary Hans, once the cameraman for the Nazi propagandist Leni Riefenstahl. Shortly after the end of World War II, Hans and his family flee to Bolivia to start over. There, the ever-restless Hans decides to embark on an expedition in search of the fabled lost Inca city of Paitití, enlisting two of his daughters to join him on his outlandish quest into the depths of the Amazon, with disastrous consequences.

Set against the backdrop of the both optimistic and violent 1950s and 1960s, Affections traces the Ertls’s slow and inevitable breakdown through the various erratic trajectories of each family member: Hans’s undertakings of colossal, foolhardy projects and his subsequent spectacular failures; his daughter Monika, heir to his adventurous spirit, who joins the Bolivian Marxist guerrillas and becomes known as “Che Guevara’s avenger”; and his wife and two younger sisters left to pick up the pieces in their wake. In this short but powerful work, Hasbún weaves a masterfully layered tale of how a family’s voyage of discovery ends up eroding the affections that once held it together.

A one-sitting tale of fragmented relationships with a broad scope, delivered with grace and power. ~Kirkus

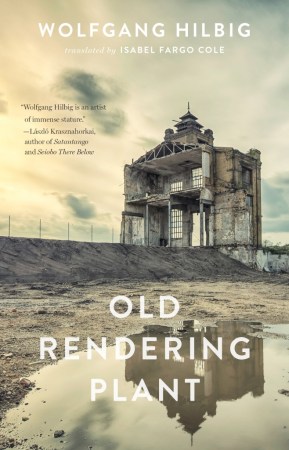

Old Rendering Plant

Old Rendering Plant

by Wolfgang Hilbig

translated from the German by Isabel Fargo Cole

(Germany, Two Lines Press)

Purchase from Amazon.

What falsehoods do we believe as children? And what happens when we realize they are lies?possibly heinous ones? In Old Rendering Plant Wolfgang Hilbig turns his febrile, hypnotic prose to the intersection of identity, language, and history’s darkest chapters, immersing readers in the odors and oozings of a butchery that has for years dumped biological waste into a river. It starts when a young boy becomes obsessed with an empty and decayed coal plant, coming to believe that it is tied to mysterious disappearances throughout the countryside. But as a young man, with the building now turned into an abattoir processing dead animals, he revisits this place and his memories of it, realizing just how much he has missed. Plumbing memory’s mysteries while evoking historic horrors, Hilbig gives us a gothic testament for the silenced and the speechless. With a tone indebted to Poe and a syntax descended from Joyce, this suggestive, menacing tale refracts the lost innocence of youth through the heavy burdens of maturity.

In the spirit of Proust’s Swann’s Way — the section of his opus that features this olfactory moment — Wolfgang Hilbig’s Old Rendering Plant is a sensory novel that uses scent to flatten time. But whereas Proust uses a teacake to evoke a French village, Hilbig uses dissolving animal corpses to evoke postwar East Germany. Old Rendering Plant, translated by Isabel Fargo Cole and published by Two Lines Press, is about a man’s experience of a decaying slaughterhouse and a river full of toxic sludge. Like Proust’s, Hilbig’s writing has a beautiful and dream-like quality. But Old Rendering Plant is about tarnished ground. Entombed in the visceral smells of the sickly landscape, the unnamed narrator floats through it in paralyzed fashion. ~Nathan Scott McNamara, Los Angeles Review of Books

I Am the Brother of XX

I Am the Brother of XX

by Fleur Jaeggy

translated from the Italian by Gini Alhadeff

(Switzerland, New Directions)

Purchase from Amazon.

Fleur Jaeggy is often noted for her terse and telegraphic style, which somehow brews up a profound paradox that seems bent on haunting the reader: despite a sort of zero-at-the-bone baseline, her fiction is weirdly also incredibly moving. How does she do it? No one knows. But here, in her newest collection, I Am the Brother of XX, she does it again. Like a magician or a master criminal, who can say how she gets away with it, but whether the stories involve famous writers (Calvino, Ingeborg Bachmann, Joseph Brodsky) or baronesses or 13th-century visionaries or tormented siblings bred up in elite Swiss boarding schools, they somehow steal your heart. And they don’t rest at that, but endlessly disturb your mind.

In Jaeggy’s world, characters don’t change or have epiphanies—unless a sudden cruelty, a murder, or a suicide counts. They are as they are, and much of what they are is related to where they’re from—the soil in which they were planted. This is especially true in Jaeggy’s stories, where social position, citizenship, and class confer on everyone a sort of generic character: foreigners en route to visit Auschwitz are laughing and “arrogant with everyone,” but, as they approach their destination, “they instantly put on an air of decorum . . . an ostentation of grief.” Young farmhands have “meek, stubborn skulls . . . . They were like brothers to the cattle.” These are reminiscent of the archetypal characters one finds in the Brothers Grimm. Particularly in Jaeggy’s earlier work, objects and settings are generalized, rarely pinned to a specific time and place: we encounter a house with a garden, a wooden cross, a pastor, incestuous twins, crystal glasses, a gauzy blue dress. ~Sheila Heti, The New Yorker

You Should Have Left

You Should Have Left

by Daniel Kehlmann

translated from the German by Ross Benjamin

(Germany, Pantheon)

Purchase from Amazon.

“It is fitting that I’m beginning a new notebook up here. New surroundings and new ideas, a new beginning. Fresh air.”

This passage is from the first entry of a journal kept by the narrator of Daniel Kehlmann’s spellbinding new novel. It is the record of the seven days that he, his wife, and his four-year-old daughter spend in a house they have rented in the mountains of Germany—a house that thwarts the expectations of the narrator’s recollection and seems to defy the very laws of physics. He is eager to finish a screenplay for a sequel to the movie that launched his career, but something he cannot explain is undermining his convictions and confidence, a process he is recording in this account of the uncanny events that unfold as he tries to understand what, exactly, is happening around him—and within him.

The new book by the German-Austrian author Daniel Kehlmann, “You Should Have Left,” is a minor trick for him, but a neat one. This mind-bending novella about a writer losing his marbles contains images that startle and linger. ~John Williams, The New York Times

Chasing the King of Hearts

Chasing the King of Hearts

by Hanna Krall

translated from the Polish by Philip Boehm

(Poland, Feminist Press)

Purchase from Amazon.

This canonical work of Polish reportage is a terse, unexpected human lesson born of an occupation-era love story. Based on a true story, the raw interplay of history and fictionalization spans the Warsaw Ghetto, the war-torn countryside, and the nightmare of Auschwitz.

Quirky and powerful treatments of the Holocaust exist in recent literature and film, but Krall’s joyous and wise Izolda gets under your skin in ways both subversive and uplifting. Thanks to Peirene Press and Philip Boehm’s glorious translation, you now have in your hands a masterpiece. ~Kapka Kassabova, The Guardian

Beyond the Rice Fields

Beyond the Rice Fields

by Naivo

translated from the French by Allison M. Charette

(Madagascar, Restless Books)

Purchase from Amazon.

The first novel from Madagascar ever to be translated into English, Naivo’s magisterial Beyond the Rice Fields delves into the upheavals of the nation’s past as it confronted Christianity and modernity, through the twin narratives of a slave and his master’s daughter.

Fara and her father’s slave, Tsito, have been close since her father bought the boy after his forest village was destroyed. Now in Sahasoa, amongst the cattle and rice fields, everything is new for Tsito, and Fara at last has a companion. But as Tsito looks forward to the bright promise of freedom and Fara, backward to a dark, long-denied family history, a rift opens between them just as British Christian missionaries and French industrialists arrive and violence erupts across the country. Love and innocence fall away, and Tsito and Fara’s world becomes enveloped by tyranny, superstition, and fear.

With captivating lyricism, propulsive urgency, and two unforgettable characters at the story’s core, Naivo unflinchingly delves into the brutal history of nineteenth-century Madagascar. Beyond the Rice Fields is a tour de force that has much to teach us about human bondage and the stories we tell to face—and hide from—ourselves, each other, our pasts, and our destinies.

The author wrote this book in French, not in Malagasy. In other words, he chose to use “vazaha words” to tell this story. And yet, the novel is not an easy one for foreigners. This is no Things Fall Apart, setting out a simple before-and-after story of how colonialism impacted Africa. Rather, Beyond the Rice Fields is a spiraling, dense, and prickly work, difficult to access until the foreign reader has agreed to put in some time and effort. But once the effort is put in, it is richly rewarding. ~Kate Prengel, World Literature Today

My Heart Hemmed In

My Heart Hemmed In

by Marie NDiaye

translated from the French by Jordan Stump

(France, Two Lines Press)

Purchase from Amazon.

Marie NDiaye has long been celebrated for her unrivaled ability to make us see just how little we understand about ourselves. My Heart Hemmed In is her most powerful statement on the hidden selves that we rarely glimpse — and are often shocked by.

There is something very wrong with Nadia and her husband Ange, middle-aged provincial schoolteachers who slowly realize that they are despised by everyone around them. One day a savage wound appears in Ange’s stomach, and as Nadia fights to save her husband’s life their hideous neighbor Noget — a man everyone insists is a famous author — inexplicably imposes his care upon them. While Noget fattens them with ever richer foods, Nadia embarks on a nightmarish visit to her ex-husband and estranged son — is she abandoning Ange or revisiting old grievances in an attempt to save him?

Conjuring an atmosphere of paranoia and menace, My Heart Hemmed In creates a bizarre, foggy world where strange coincidences, harsh cruelty, and constantly shifting relationships all seem part of some shadowy truth. Surreal, allegorical, and psychologically acute, My Heart Hemmed In shows a masterful author giving her readers her most complex and compelling world yet.

Realistically chilling in spite of — and because of — their absurdity and lingering mystery, Marie NDiaye’s novels are becoming ever more important to me as they look deeply into the hearts of troubled individuals, fighting against their very selves. My Heart Hemmed In is the latest to be translated into English, and it is my favorite. I suspect, though, that that’s only in part due to the book itself. I’m sure the other part is that I’m becoming more in tune with what NDiaye is doing, more adept at reading her strange tales, so I’m getting more out of each book. Certainly, I loved this one from page one until the end, reading it almost non-stop over a few otherwise hazy days in July. ~Trevor Berrett, The Mookse and the Gripes

Savage Theories

Savage Theories

by Pola Oloixarac

translated from the Spanish by Roy Kesey

(Argentina, Soho Press)

Purchase from Amazon.

A debut novel of seduction and madness, hate and love, set in the world of Argentine academia and animated by the spirits of Wittgenstein, Rousseau, Nabokov and Bolaño.

Rosa Ostreech, a pseudonym for the novel’s beautiful but self-conscious narrator, carries around a trilingual edition of Aristotle’s Metaphysics, struggles with her thesis on violence and culture, sleeps with a bourgeois former guerrilla, and pursues her elderly professor with a highly charged blend of eroticism and desperation. Elsewhere on campus, Pabst and Kamtchowsky tour the underground scene of Buenos Aires, dabbling in ketamine, group sex, video games, and hacking. And in Africa in 1917, a Dutch anthropologist named Johan van Vliet begins work on a theory that explains human consciousness and civilization by reference to our early primate ancestors—animals, who, in the process of becoming human, spent thousands of years as prey.

Savage Theories wryly explores fear and violence, war and sex, eroticism and philosophy. Its complex and flawed characters grapple with a mess of impossible, visionary theories, searching for their place in our fragmented digital world.

While there are echoes of Borges and Bolaño here, the synthesis of ideas and the manic intelligence are wholly new. Brilliant, original, and very fun to read. ~Kirkus

August

August

by Romina Paula

translated from the Spanish by Jennifer Croft

(Argentina, Feminist Press)

Purchase from Amazon.

Traveling home to rural Patagonia, a young woman grapples with herself as she makes the journey to scatter the ashes of her friend Andrea. Twenty-one-year-old Emilia might still be living, but she’s jaded by her studies and discontent with her boyfriend, and apathetic toward the idea of moving on. Despite the admiration she receives for having relocated to Buenos Aires, in reality, cosmopolitanism and a career seem like empty scams. Instead, she finds her life pathetic.

Once home, Emilia stays with Andrea’s parents, wearing the dead girl’s clothes, sleeping in her bed, and befriending her cat. Her life put on hold, she loses herself to days wondering how if what had happened—leaving an ex, leaving Patagonia, Andrea leaving her—hadn’t happened.

Both a reverse coming-of-age story and a tangled homecoming tale, this frank confession to a deceased confidante. A keen portrait of a young generation stagnating in an increasingly globalized Argentina, August considers the banality of life against the sudden changes that accompany death.

August demonstrates how loss can mark a person, how it can permeate everything, and what we can do with it. ~Lauren Kinney, Los Angeles Review of Books

The Magician of Vienna

The Magician of Vienna

by Sergio Pitol

translated from the Spanish by George Henson

(Mexico, Deep Vellum)

Purchase from Amazon.

The heartbreaking final volume in Sergio Pitol’s groundbreaking memoir-essay-fiction-hybrid “Trilogy of Memory” finds Pitol boldly and passionately weaving fiction and autobiography together to tell of his life lived through literature as a way to stave off the advancement of a degenerative neurological condition causing him to lose the use of language. Fiction invades autobiography—and vice versa—as Pitol writes to forestall the advancement of degenerative memory loss.

There are times in which not translating an author is an act of injustice. This is the case of Sergio Pitol, one of Mexico’s most important and revered writers, whose books are finally being published in English decades after their original publication. ~Ignacio M. Sánchez Prado, Los Angeles Review of Books

The Iliac Crest

The Iliac Crest

by Cristina Rivera Garza

translated from the Spanish by Sarah Booker

(Mexico, Feminist Press)

Purchase from Amazon.

On a dark and stormy night, two mysterious women invade an unnamed narrator’s house, where they proceed to ruthlessly question their host’s identity. While the women are strangely intimate — even inventing a secret language — they harass the narrator by repeatedly claiming that they know his greatest secret: that he is, in fact, a woman. As the increasingly frantic protagonist fails to defend his supposed masculinity, he eventually finds himself in a sanatorium.

Published for the first time in English, this Gothic tale destabilizes male-female binaries and subverts literary tropes.

The Iliac Crest is an intelligent and unforgettable piece of queer literature. It sits with you like the overwhelming sound of ocean waves crashing into your auditory system for the first time. ~Rios de la Luz, World Literature Today

Fever Dream

Fever Dream

by Samanta Schweblin

translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell

(Argentina, Riverhead)

Purchase from Amazon.

A young woman named Amanda lies dying in a rural hospital clinic. A boy named David sits beside her. She’s not his mother. He’s not her child. Together, they tell a haunting story of broken souls, toxins, and the power and desperation of family.

Fever Dream is a nightmare come to life, a ghost story for the real world, a love story and a cautionary tale. One of the freshest new voices to come out of the Spanish language and translated into English for the first time, Samanta Schweblin creates an aura of strange psychological menace and otherworldly reality in this absorbing, unsettling, taut novel.

This is a cautionary tale that tells us, in eloquently odd terms: being a parent is a scary business. ~Lee Monks, The Mookse and the Gripes

Ghachar Ghochar

Ghachar Ghochar

by Vivek Shanbhag

translated from the Kannada by Srinath Perur

(India, Penguin)

Purchase from Amazon.

A young man’s close-knit family is nearly destitute when his uncle founds a successful spice company, changing their fortunes overnight. As they move from a cramped, ant-infested shack to a larger house on the other side of Bangalore, and try to adjust to a new way of life, the family dynamic begins to shift. Allegiances realign; marriages are arranged and begin to falter; and conflict brews ominously in the background. Things become “ghachar ghochar”—a nonsense phrase uttered by one meaning something tangled beyond repair, a knot that can’t be untied.

Elegantly written and punctuated by moments of unexpected warmth and humor, Ghachar Ghochar is a quietly enthralling, deeply unsettling novel about the shifting meanings—and consequences—of financial gain in contemporary India.

The book in our hands is elegant, lean, balletic — but how can we know if the essence of the original has been communicated? When this question has been put to Vivek Shanbhag, who has himself also worked as a translator, he has recalled one particular passage from the novel. It is, notably, one of the scenes he added specifically for the translation. The narrator’s wife has gone out of town and he is idly rifling through her closet, touching her clothes, her jewelry. He catches scent of her suddenly. He presses his face into her saris to smell more, but the closer he gets, the more the smell retreats. “Whatever fragrance the whole wardrobe had was missing in the individual clothes it held. The more keenly I sought it, the further it receded. A strange mixture of feelings I could not quite grasp — love, fear, entitlement, desire, frustration — flooded through me until it seemed like I would break.” ~Parul Sehgal, The New York Times

For Isabel: A Mandala

For Isabel: A Mandala

by Antonio Tabucchi

translated from the Italian by Elizabeth Harris

(Italy, Archipelago)

Purchase from Amazon.

A metaphysical detective story about love and existence from the Italian master, Antonio Tabucchi. When Tadeus sets out to find Isabel, his former love, he soon finds himself on a metaphysical journey across the world, one that calls into question the meaning of time and existence and the power of words.

Isabel disappeared many years ago. Tadeus Slowacki, a Polish writer, her former friend and lover, has come back to Lisbon to learn of her whereabouts. Rumors abound: Isabel died in prison under Salazar’s regime, or perhaps wasn’t arrested at all. As Tadeus interviews one old acquaintance of hers after the next, a chameleon-like portrait of a young, ideological woman emerges, ultimately bringing Tadeus on a metaphysical journey across the continent. Constructed in the form of a mandala, For Isabel is the spiraling search for an enigma, an investigation into time and existence, the power of words, and the limits of the senses. In this posthumous work Tabucchi creates an ingenious narration, tracing circles around a lost woman and the ultimate inaccessible truth.

It takes a while to ‘break into’ this thoughtful, dreamlike novel, but I found myself being submerged by its elusive mystery. The conclusion is stunning, brilliant and well worth the read. ~Guy Savage, His Futile Preoccupations

Ebola 76

Ebola 76

by Amir Tag Elsir

translated from the Arabic by Charis Bredin

(Sudan, Darf Publishers)

Purchase from Amazon.

A darkly satirical portrayal of the outbreak of Ebola in 1970s Congo and Sudan. Humorous and tragic in turns, the narrative weaves its way from the graveyards of Kinshasa to the factories, brothels and ex-pat communities of southern Sudan, as the disease selects its victims from amongst the novel’s vibrant and eccentric characters.

Like a medieval danse macabre, Ebola leads a parade of wretches to the grave, but Tag Elsir’s apparent disdain for his characters robs his narrative of empathy and leaves the reader indifferent to the fate of Lewis, the blind guitarist Ruwadi, the washed?up magician Jamadi and the rest. Empathy isn’t the only possible approach to such horror, but it’s the natural response for many readers and we may feel uncomfortable without it. ~Jane Housham, The Guardian

The Last Bell

The Last Bell

by Johannes Urzidil

translated from the German by David Burnett

(Germany, Pushkin Press)

Purchase from Amazon.

A maid who is unexpectedly left her wealthy employers’ worldly possessions, when they flee the country after the Nazi occupation; a loyal bank clerk, who steals a Renaissance portrait of a Spanish noblewoman, and falls into troublesome love with her; a middle-aged travel agent, who is perhaps the least well-travelled man in the city and advises his clients from what he has read in books, anxiously awaits his looming honeymoon; a widowed villager, whose ‘magnetic’ (or perhaps ‘crazy’) twelve-year-old daughter witnesses a disturbing event; and a tiny village thrown into civil war by the disappearance of a freshly baked cheesecake – these stories about the tremendous upheaval which results when the ordinary encounters the unexpected are vividly told, with both humour and humanity. This is the first ever English publication of these both literally and metaphorically enchanting Bohemian tales, by one of the great overlooked writers of the twentieth century.

In Urzidil’s new home, the water was a little reminder of the one he left behind. But while Shakespeare’s Bohemia is a total fiction (it’s not a desert), Urzidil’s remembered county is a blend of the fact and the fantasy that make up memory. His writing questions what it is to be a human and to remember. And what it means to love your homeland when extreme “patriotism” is precisely why it is gone. ~James Reith, The Atlantic

Radiant Terminus

Radiant Terminus

by Antoine Volodine

translated from the French by Jeffery Zuckerman

(France, Open Letter Books)

Purchase from Amazon.

The most patently sci-fi work of Antoine Volodine’s to be translated into English, Radiant Terminus takes place in a Tarkovskian landscape after the fall of the Second Soviet Union. Most of humanity has been destroyed thanks to a number of nuclear meltdowns, but a few communes remain, including one run by Solovyei, a psychotic father with the ability to invade people’s dreams — including those of his daughters — and torment them for thousands of years.

When a group of damaged individuals seek safety from this nuclear winter in Solovyei’s commune, a plot develops to overthrow him, end his reign of mental abuse, and restore humanity.

Fantastical, unsettling, and occasionally funny, Radiant Terminus is a key entry in Volodine’s epic literary project that — with its broad landscape, ambitious vision, and interlocking characters and ideas — calls to mind the best of David Mitchell.

This does seem likely to be the sort of book that not all readers will take to: some presumably want more action in their dystopian nightmare-visions (though Radiant Terminus is certainly vivid enough in those), some will be annoyed by Solovyei’s powers (as if authors didn’t always have the same complete and, whenever they want, arbitrary control over fiction-actions …), and there will be readers for whom the violation scenes (and themes) will be too disturbing. Yet despite any possible objections, it’s hard not to see Radiant Terminus as a truly grand work. ~M.A. Orthofer, The Complete Review

Remains of Life

Remains of Life

by Wu He

translated from the Chinese by Michael Berry

(Taiwan, Columbia University Press)

Purchase from Amazon.

On October 27, 1930, during a sports meet at Musha Elementary School on an aboriginal reservation in the mountains of Taiwan, a bloody uprising occurred unlike anything Japan had experienced in its colonial history. Before noon, the Atayal tribe had slain one hundred and thirty-four Japanese in a headhunting ritual. The Japanese responded with a militia of three thousand, heavy artillery, airplanes, and internationally banned poisonous gas, bringing the tribe to the brink of genocide.

Nearly seventy years later, Chen Guocheng, a writer known as Wu He, or “Dancing Crane,” investigated the Musha Incident to search for any survivors and their descendants. Remains of Life, a milestone of Chinese experimental literature, is a fictionalized account of the writer’s experiences among the people who live their lives in the aftermath of this history. Written in a stream-of-consciousness style, it contains no paragraph breaks and only a handful of sentences. Shifting among observations about the people the author meets, philosophical musings, and fantastical leaps of imagination, Remains of Life is a powerful literary reckoning with one of the darkest chapters in Taiwan’s colonial history.

Wu He’s narrative is an outpouring, and only to a limited extent a story; the fascinating historical events and his encounters do make for an often engaging read, and his efforts to consider both the Mushu Incident and its aftermaths are fascinating — but it is not easy to get through. Too lively and varied to be a slog, Remains of Life also remains a frustratingly slippery text. ~M.A. Orthofer, The Complete Review

Leave a Reply