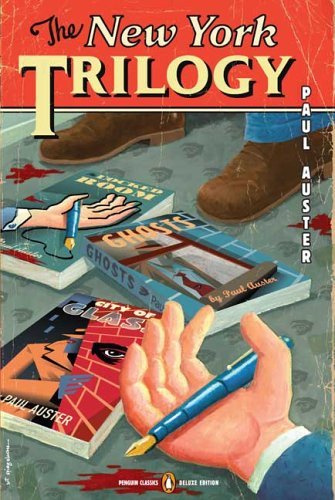

The New York Trilogy

by Paul Auster (1987)

Penguin Classics (2006)

308 pp

It seems that by writing these reviews I’m actually making my ignorance increasingly apparent. See, this is the first book by Paul Auster that I’ve read. Thankfully, I can (sort of) say that I’ve read three of Auster’s books as this is a “trilogy.” Here we have three pieces: “City of Glass” (1985), “Ghosts” (1986), and “The Locked Room” (1986). The three were compiled almost right away (which was the point all along) into a single work: The New York Trilogy. Indeed, even while they were being written they were referred to as The New York Trilogy. While all three are unique, each also ties to themes and even passages of another. I’d go so far as to say that in order to fully enjoy them, they should each be read and in order (and maybe read again). I feel I had the good fortune to read it in one of its newest editions with a pulp feel and cover art from Art Speigelman.

Let me first give a brief introduction to each story. Here’s my feeble attempt at a compelling blurb!

City of Glass: The first story is also the longest, coming in at 130 pages in my edition. Daniel Quinn is a mystery writer who lost his wife and young son a few years ago in an accident. Lonely, he almost feels more at home in his pen-name William Wilson, or even in his character’s persona. One late night, he gets a phone call for a Paul Auster, the detective. Quinn tells the caller he’s not the man, but then he wishes he’d have played along for a while. Fortunately, he gets his chance. Assuming the identity of Paul Auster, Quinn accepts a strange assignment involving metaphysical elements from Genesis, Don Quixote, Humpty-Dumpty, and more. The questions we ask are pulled up from the level of the story itself to the nature of story, the writing of it, etc.

Ghosts: Blue is a detective, trained by Brown. White hires Blue to spy on Black. Blue knows next to nothing about what he’s looking for, so he sets up shop in an apartment across the street from Black’s apartment in Brooklyn. Not much happens — on the outside, anyway. However, Blue is not necessarily bored. On the contrary, he comes to know himself better than before.

The Locked Room: The first-person narrator in this story is contacted by Sophie, the wife of Fanshawe, his best friend during childhood (I caught the references to Hawthorne, but I don’t know what they mean). Fanshawe has disappeared, months ago, in fact. It’s so uncharacteristic of him that the narrator and Sophie assume he’s dead. It’s been years since the narrator had any contact with Fanshawe, and he feels he doesn’t know him at all anymore. Nevertheless, shortly before he disappeared Fanshawe gave his wife all of his writings and told him to contact the narrator if something should happen to him. Turns out that the writings are brilliant, and the narrator and Sophie are falling in love.

The strange thing about the blurbs above is that they sound sort of like hard-boiled detective novels. That’s not the case though. The basics of the plot intentionally play with elements from classic crime, but these books dwell on the metaphysical. And Auster’s writing is at once clear and poetic (not always the case when dealing with books that ask questions beyond their capacity to answer).

Interestingly, just when I thought “City of Glass” and “Ghosts” were already working layers and layers above the actual stories, “The Locked Room” pulls the perspective up even further, leaving more questions.

So, how does New York play into this? First and foremost, that’s where the stories are set, for the most part. But there’s more to it, especially in “City of Glass.”

New York was an inexhaustible space, a labyrinth of endless steps, and no matter how far he walked, no matter how well he came to know its neighborhoods and streets, it always left him with the feeling of being lost. Lost, not only in the city, but within himself as well. Each time he took a walk, he felt as though he were leaving himself behind, and by giving himself up to the movement of the streets, by reducing himself to a seeing eye, he was able to escape the obligation to think, and this, more than anything else, brought him a measure of peace, a salutary emptiness within.

Besides presenting the city as a sort of motif within which to explore metaphysical ideas, Auster also uses this opportunity to present some of New York’s fascinating history. For example, stories about where Poe, Witman, Thoreau, and others sat and pondered, are slyly inserted into the trilogy, shedding light on the mood while presenting more questions. Tales about the architecture, in particular about the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, are inserted in ways that both give a sense of place and a sense of the psychology of the character.

I was not sure what I was getting into when I opened up to the first story “City of Glass.” To be honest, I’m not sure what I got after finishing all three pieces. Indeed, and I don’t think it’s a spoiler to say this, the answer to all of the questions I came up with were not answered. At the end of each story I found myself asking, “What about this? What about that?” Don’t most mystery novels tie up the loose ends? Is Auster just fooling with me? Believe me, though, I was grinning while I was asking those questions. These stories are unsatisfying in the most satisfying way. Where most mysteries end up falling short of the reader’s expectations when full disclosure is made, these excellent pieces allow the reader to keep on searching.

On a side note, I do like those Penguin Classics Deluxe editions. They’re attractively made, and mysteriously cheap in foreign bookshops.

That said, Penguin are really overdoing the reissuing & repackaging thing these days.

Anyway, Paul Auster…

Since you are being honest, Trevor, I too have a New York Trilogy/Auster story. I’d heard about it but never read it so when the Folio Society produced a deluxe edition (and it is wonderful) I ordered it. Picked it up three weeks after it arrived for a good long read — there were eight blank pages (four sets of two), which I couldn’t quite figure out. Phoned around to some friends to see if this was deliberate (in some ways, it seemed possible) or some misprint — those who had read the book said it was a long time ago and they didn’t remember any blank pages. I finally had to sneak off to a bookstore to confirm that I did in fact have a defective copy. I’ll give the Folio Society credit as a quick email produced a complete copy. I feel only mildly chagrined that I had to wonder about it.

For me, Auster in this work is like the writing version of a molecular scientist. He takes a slice of the sample he is analyzing, very carefully prepares it and then puts it under the microscope to examine it in detail. In this case, there are three such slices. The result is a very detailed awareness of the slice and an equal awareness that what we do know is incomplete. I quite like that, but for anyone who likes a book to end with a resolution, Auster is not their author. When you close the book, you have only started the process — and what I remember best about this work is, in fact, New York and the way he has used his stories to start an examination of the city. I did read it twice on first exposure and it is still in the pile awaiting another read. As I said elsewhere, I’m pretty sure Auster is someone that I have to be in the right mood to understand and appreciate.

Rob, I agree that the Penquin Classics Deluxe editions are attractive (for the most part), but that Penguin is overdoing it a bit. It seems every time I go to the bookstore there is a new edition of some book I just picked up!

And Kevin, well put! I’m anxious to read this one again now that I have a better feel for what’s coming, and I hope to pick up more about New York this next time around. Thankfully, I was in the mood for Auster this time around, and I think when I move on to his next book I will be in the right mood then too.

By the way, I may read the rest of Auster in order, but which titles stand out to you?

It’s funny how no matter how well read we may be, the volume of that which we haven’t read is always so much greater than that which we have.

And that’s true even if we just stick to great works, if you’re fond of the odd bit of crime or SF as I am the problem becomes even worse.

Anyway, I’ve read Auster’s Leviathan which I was very impressed by. It’s still a novel about novelists, with embedded stories forming part of its narrative, but it’s less metaphysical than these sound although like these it demands a more than merely passive reader. If you feel like more Auster some time Leviathan is well worth checking out.

I actually have The New York Trilogy unread at home, I doubt I’ll get to it in the next couple of months but I do look forward to it more having now read your thoughts than I was previously, he’s a marvellous writer and at his best very thought provoking.

Max, the sooner you get to it, the better for me! I’m still trying to interpret it.

Speaking of which, Kevin, what are some of your interpretations? About New York? About authorship? About anything in the novels. This goes for anyone who wants to respond, but I wouldn’t mind getting my ideas some structure as I respond to others’.

Its been some time since I read the book and I want to go back for some reminders before offering thoughts. I’m tied up with Giller stuff for a day or two but promise they will be posted soon.

Whenever you get the time and the will, Kevin. If there are other things to get through, don’t let this interrupt your schedule!

I’ve sent a link to a TLS review of Auster’s most recent book which I would appreciate if you would post (since I don’t know how) as a reference for this comment.

The part of the review that I want to begin from is midway through — a reference that for Auster being two-dimensional is a quality not a curse. I think that applies to all his work — I think it is key to my feeling about The New York Trilogy.

What is apparent in each of these three linked books is what I would call “absence” — it is not that the relationships (or indeed events) are dysfunctional, but rather they are non-functional, because an obvious element or elements is/are missing. That absence (the third dimension from the review language) is to me Auster’s greatest strength in this trilogy. Like Kafka, in some ways, because there is the unexplained — unlike Kafka, where it is there but not understood, in Auster’s case it is simply not there. The challenge — and the reward — to the reader is the chance to contemplate what that third dimension might look like.

I think the same reasoning applies to the New York that supplies the geography for this book. Note, for example, that the walking patterns which are mapped effectively turn the city from three dimensions into two (a most interesting literary device). For me, as a more than occasional visitor to New York, the two-three dimension concept struck a particular chord. I have always felt when I am there that I am mixing with groups of people who I kind of understand, but really don’t — that the city is a backdrop for an immense number of relationships and happenings that overlap, like a Venn diagram, but never really touch. (Go to Rockefeller Center, or the Park, someday; watch the people that pass you by; and imagine their life.) The only thing they have in common is that they are happening in the same geographical space. Auster’s detailed, two-dimensional portrayals in the Trilogy — with the obvious missing third dimension — capture that feel. What I love about this work, and his other books when I am in the mood for them, is that when you put the book down you have just started to get the experience. You can build any number of third dimensions.

Here is the link Kevin refers to above.

Excellent thoughts Kevin. Unfortunately, I don’t have time right now to respond, but I will!

Just having read a piece on Paul Auster’s Man in the Dark in the New York Review of Books, I thought I’d post the link.

A bit late but probably, Aside from the New York Trilogy, I strongly suggest The Music of Chance. I also liked Timbuktu a lot but opinion seems to be divided on that book. In the Country of last things is another which kept me gripped.

I would avoid reading The Book of Illusions and Oracle Night back to back. Although they stand alone as great novels they share way too many similarities.

For some reason I made the goal of reading all of Auster’s work in publication order, which means my next one is In the Country of Last Things. I have it on the shelf but haven’t started it yet. I imagine I’ll keep to my goal with Auster, though that means it could be a long time before I get to some of his later work.