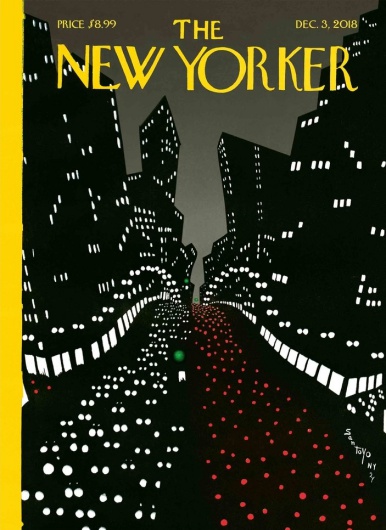

“Snowing in Greenwich Village”

by John Updike

from the January 21, 1956 issue of The New Yorker

reprinted in the December 3, 2018 issue of The New Yorker

This week, rather than publish a new story, The New Yorker went back to their archives to give us a story by Jean Stafford, who died in 1979, and John Updike, who died in 2009. This is a rare instance, then, where I’ve read both stories and have even written about one of them. For Jean Stafford’s “Children Are Always Bored on Sunday,” click here.

This week, rather than publish a new story, The New Yorker went back to their archives to give us a story by Jean Stafford, who died in 1979, and John Updike, who died in 2009. This is a rare instance, then, where I’ve read both stories and have even written about one of them. For Jean Stafford’s “Children Are Always Bored on Sunday,” click here.

Updike’s “Snowing in Greenwich Village” is Updike’s first story about the Maples. He’d write about Richard and Joan Maples eighteen times in all, tracking the ups and downs of their marriage over time (the final story is “Grandparenting”).

In “Snowing in Greenwhich Village” Joan and Richard have been married for “nearly” two years, and Richard “was still so young-looking that people did not instinctively lay upon him hostly duties.” Who are the Maples hosting? Rebecca Cune.

It’s a strange evening — the Maples’ first in their new place in Greenwich Village. Rebecca, a natural raconteur, tells stories, while Joan and Richard listen, unable to match her odd experiences. But there is a moment of connection when they look out the window and see it’s snowing. Soon Rebecca says “I think I’d best go.”

“Please don’t,” Joan said with an urgency Richard had not expected; clearly she was tired. Probably the new home, the change in the weather, the good sherry, the currents of affection between herself and her husband that her sudden hug had renewed, and Rebecca’s presence had become in her mind the inextricable elements of one enchanting moment.

For Richard, though, the moment is different. He can see Rebecca’s retelling, in which the Maples, Joan in particular, are themselves the odd ingredient. In this subtle way, Richard starts to align himself more with Rebecca than with his wife.

This is exacerbated when Joan herself demands Richard walk Rebecca home since it is snowing. When they get there, Rebecca invites him to come see her place.

Richard’s suspicion on the street that he was trespassing beyond the public gardens of courtesy turned to certain guilt.

Of course, nothing has happened, but Richard’s picking up on a lot of potential signs, like when Rebecca says, “It’s hot as hell in here,” the first time she’s sworn in front of him.

This is Updike territory, of course: infidelity, even when there is no overt act. He can write it well. But it’s never been a story I’ve particularly taken to, even less over the past decade or so when these stories of “men being men” have shown themselves to be more than problematic.

“Snowing in Greenwich Village” is a line of subtle clues Richard interprets as invitations. Are they, though? Is Rebecca making herself available to Richard right after they’ve left Joan? Perhaps. Perhaps not.

Of course, nothing happens in the end. Richard leaves. But he still feels he avoided something Rebecca was ready for. And Updike likewise suggests he sees it all as just short of inevitable: “Oh, but they were close.”

I’m very curious to hear how you all respond to Updike’s tale of avoidance. Please leave your comments below!

I couldn’t help but think that this belongs in the archive–it almost seems like a parody of what New Yorker fiction once was–liquored-up, sophisticated cosmopolitan types and the whiff of adultery all set in what that magazine and writer seemed to view as the center of the universe–Manhattan. Certainly well-written, but I can’t see any reason to exhume this except as a relic.

Maybe it’s a generational thing but I appreciated both archive stories. Both stories let the reader decide how these relationships will pan out. I think the stories are timeless.

I liked the Jean Stafford story quite a bit.

True, it has the essense of a typical New Yorker short story, the well-educated wealthy trust fund set talking about nothing in particular over sherry.

The possibility of infidelity in 1956 is so relatively innocent compared to how that would have played out today.

Updike has an easy smooth style and writes pitch perfect 1950’s dialogue and a nice contrast between a married couple’s more ample apartment contrasted with a single woman’s more cramped compact living space

From which she will probably move out of once she’s snagged a man or never will. There is a nice ambiguity about it all. The wife having a cold. Her husband looking too young and Rebecca looking better than the husband’s wife. All this diuring light snowstorm.

The writing is very smooth and apt for the situation and the story has such an easy flow to it. But there is a bland superficiality about the whole thing. Updike had the ability to write well about anything yet it all doesn’t add up to much or is a small part of something larger.

It is a good contrast to all the me-too type harassment stories and so much more innocent. It is interesting for its writing style which kind of makes up for not much in the way of content.

I love this story as a history piece and putting the reader into that moment capturing the zeitgeist. This is the 1950s and imagining the world around these people as their lives are starting to take shape. The reader can imagine what may be going through the heads of the characters but we are not completely sure which leaves us wanting to learn more. The Modigliani and da Vinci comparisons bring beauty and art right into the visual thought dream of the reader and modernism of the times .. Imagine the clothing styles … cool casual indoor smoking chic, romanticism of the colored snowfall atmospheric descriptions of cold and warm and hot .. temperatures flaring.